Urban farming and beekeeping have become increasingly more discussed and for good reason. Communities all over the world are reclaiming urban spaces for agricultural projects, often community oriented, like the Prinzessinnengarten, in Kreuzberg, Berlin or Keep Growing Detroit, in Detroit USA. There is a noticeable yearning in the air to replace the pre-packaged supermarket culture, which has been seemingly forced upon us, with a culture that brings us closer to and strengthens our connection to the food we consume.Nestled off a busy roundabout in Kreuzberg sits the Prinzessinnengarten. It’s very easy to forget that the garden is sandwiched between major roads as you sip your coffee or root juice (Wurzel Saft) and admire the plants, birds and bees. The garden has prompted for a program of exchange by attracting artists, students, neighborhood organizations, schools and kindergartens.

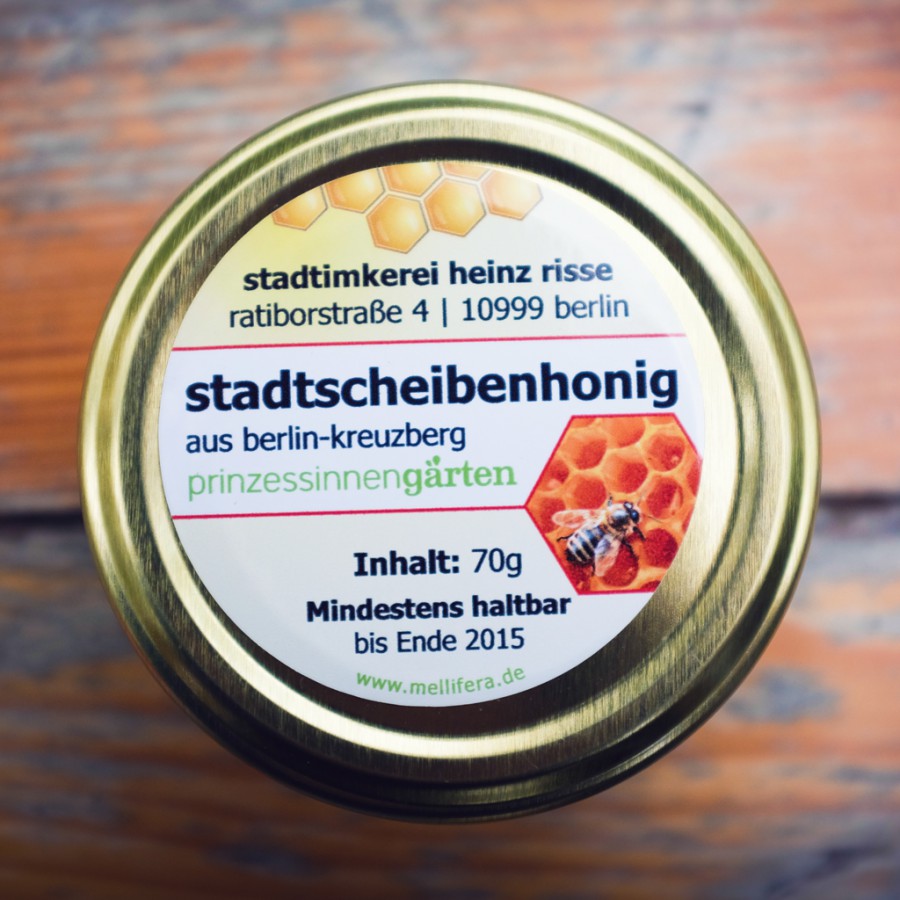

Delicious homemade vegetarian, vegan meals and cakes are available made with produce grown in the garden. Thursdays and Saturdays are Community Garden Days where anyone can go along and help out around the garden. Community is the core motivation of this garden – it aims to promote a responsible use of resources and encourages sustainable neighborhood and urban development.Prinzessinnengarten is home to a number of beehives belonging to Heinz Risse. Heinz is one of 500 beekeepers in Berlin who collectively produce up to 150 tons of honey per year. His aim is to transform beekeeping into a natural, basic and sustainable practice. We met up with Heinz in the Prinzessinnengarten to talk bees:

Beekeeping in cities seems to be gaining popularity…

Beekeeping in Berlin and other big cities make perfect sense. There is a great diversity in plant life, with plenty of flowers, plants and trees, slightly warmer climates and no pesticides. As opposed to the countryside where pesticides are used heavily and the main crops are monocultures, where only a single crop is cultivated like apples and rapeseed. Once the blossom from the crops has disappeared, the bees struggle to find food. This can mean the beekeepers have to transport the bees elsewhere. Extraordinarily, honey made in the city can contain up to 500 different types of pollen.

When did your interest in beekeeping begin?

I learnt beekeeping when I was a child of about 9 or 10 in Sauerland, Germany – my father was a beekeeper. I often helped him after I’d finished school. I would go up the tree whilst my father held the ladder and catch the bees with a net and small box. This was actually quite easy, if you manage to get the queen bee in the box, all the other bees will follow. I’d never had bees of my own and when my father died in 2007, I thought “oh, now it’s too late”, but I tried to find a place in Berlin and found the Prinzessinnengarten – so I transported the bees from Sauerland to Berlin. I started off with four hives and now I have about ten.

What are some of the biggest threats to the bee population?

Humans. We see the bee as an economic factor – trying to get more honey from them is a bad idea. Traditional beekeepers remove their honey and feed them with sugar water, this is neither sustainable nor healthy – it’s a bit like a human living on Haribo sweets. Queen bee breeding is also a huge problem – it shortens the gene pool by creating multiple colonies from one queen and results in no diversity. In 1920 Rudolph Steiner said that if we continue with sugar feeding and queen bee breeding, the bee will not be with us in 100 years – now we are very close to that prediction. Bees will only survive if we create hives for them. If we don’t do this, they can’t find places to live – we put a number on every tree and if we don’t like the look of the tree, we cut it down. There is far too much interference.

Other than us humans interfering, what’s going wrong?

The only way to get back to nature is to involve nature. We exist totally apart from nature right now. We think, “we can go to the supermarket and buy some cheap honey”, without thinking about the consequences of buying this cheap honey – consequences that affect all of us. The cheapest honey in the supermarket is most likely from overseas and is much cheaper than local honey. That’s what I don’t understand – honey produced overseas is cheaper than local honey. This means there’s a whole chain of people who need to earn money from it – the beekeeper, the transport, the supermarket. How does that work? We need to change the structures in our life, it’s not sustainable, and we can’t live like this.

As it stands there is no law in Germany requiring producers to say where the honey originates. For this reason, the honey is likely imported from a place where it is produced industrially and less ethically. The result is a cheaper jar of honey.

Are the positive changes that are being made good enough?

I’m not really satisfied but I’m optimistic. I get so much positive feedback from the students doing my beekeeping courses but I still know that it’s not enough. We need to change our overall culture for everyone, if we don’t, the bees will disappear. If you’re interested in starting your own beehives, Heinz runs beekeeping courses at the Prinzessinnengarten. See here for more details. Posted by Lillie in June 2014.